My story of turning Pittsburgh into another Algeria. (By Anouar Rahmani)

Four years ago, I arrived in Pittsburgh: eyes full of fear, a pale face, trembling hands. I had just fled persecution that lasted 14 years of my life in Algeria, because of my human-rights activism, my banned books, and my ideas that had long been described as licentious, deviant, and heretical. I fled a world that demonized me for speaking my mind, to land in a country where I did not know what awaited me, but I trusted blindly, out of gratitude, the organization that brought me here. The weather was cold and snowy, so I did not expect Pittsburgh to resemble Algiers in any way. And when I saw the river frozen for the first time, I lost hope that it could be my new Algiers. For Algeria, where the sun blooms every day as if it were a new sun, water does not freeze.

Perhaps one does not realize that in exile, homelands are not left behind; rather, we re-interrogate them in the new worlds. Like a mirage, we see them from time to time, dancing for us in the shadows of things. It has nothing to do with longing, obsession, pain, or patriotism either. It is deeper than that: it is a moment of pride mixed with cortisol, in which the exile tries to recreate the homeland, tries to be a god, because nothing satisfies the brokenness that follows exile in the soul except becoming a god and a creator. Thus, like a broken-spirited god, and with pride, I carried Algeria’s crooked rib with me, that painful rib with which to recreate Pittsburgh.

I arrived at City of Asylum, a big house, but the only house without a name. A yellow door and a wall without drawings, unlike the other houses; a hidden house, lonely and gloomy, but unique and exceptional. it resembled me. When people asked me which house I lived in, I would say ‘happily’: “In the house with no name”. With time, my enthusiasm waned, and I began pointing with my index finger at the Coma house in front, so as not to stir sensitivities. There were no east-facing windows in my house, where Algeria is; all the windows looked west, as if the new place wanted me to forget where I came from. But everything in Pittsburgh later revealed itself as Algerian in a way I had not expected. And just as Algeria and America share the same zodiac sign, both countries celebrate their independence in July; perhaps Pittsburgh and Algiers grew from the same placenta.

When my feet touched this frozen land, some flowers of the Atlas Mountains sprouted on Mount Washington, and at jazz events in “Alphabet City” I met world-famous writers and actors: Orhan Pamuk, Ben Okri, Mark Rylance, and many others. When they learned that I was from Algeria, they devoted a respectable amount of time, at dinner parties, to talking about it: about Algerian literature, Algerian philosophy, Algerian cinema. Above all, about Albert Camus, Frantz Fanon, Jacques Derrida, Assia Djebar, Kateb Yacine; about the Algerian revolution and how it affected the world. And the classics of Algerian cinema, foremost among them the Algerian-Italian film, The Battle of Algiers. Others told me about Cervantes living in captivity in Algiers and writing some of his novel Don Quixote there, and about the Barbary Coast wars, and before that about Berber philosophers and writers from Algeria in bygone eras such as Saint Augustine, Saint Monica, Lucius Apuleius, and others. And in the openings of the events, there was the history of ICORN International network for Writers at Risk, under whose umbrella the City of Asylum Pittsburgh organization falls, this global network previously known as the Writers’ Parliament, which was founded by Salman Rushdie and his companions, was originally aimed at saving writers and journalists in Algeria during the civil war in the 1990s, then it developed to include other countries. For Algeria, everything began, then, I wondered to myself, so did I really leave Algeria?

If we were honest, everything began in Algeria in the first place. After Algeria’s independence in 1962, when the city of Algiers turned into a destination for revolutionaries and global intellectuals. After a war of liberation from the yoke of a colonialism that lasted one hundred and thirty-two years, during which millions of Algerians were killed, in a mass genocide, and through an armed revolution that lasted seven years in which women participated strongly, and that received great international support from major figures such as the painter Picasso, the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the surrealist artist Dali. And the arrival of Frantz Fanon from the island of Martinique to Algeria as a psychiatrist, and his transformation in Algeria into a philosopher, and his joining the National Liberation Front and his choosing to be Algerian and his work as an ambassador for the Algerian Provisional Government, and after he fell ill with leukemia he asked to be buried in his new homeland whose making he had helped shape, Algeria, and that is what happened. Thus Algeria became a global symbol of liberation and struggle, and many figures flocked to it seeking asylum and support, among them even Americans, and this is what made me say to Americans, sometimes sarcastically, that with me being a refugee here in America, you are only repaying me a favor.

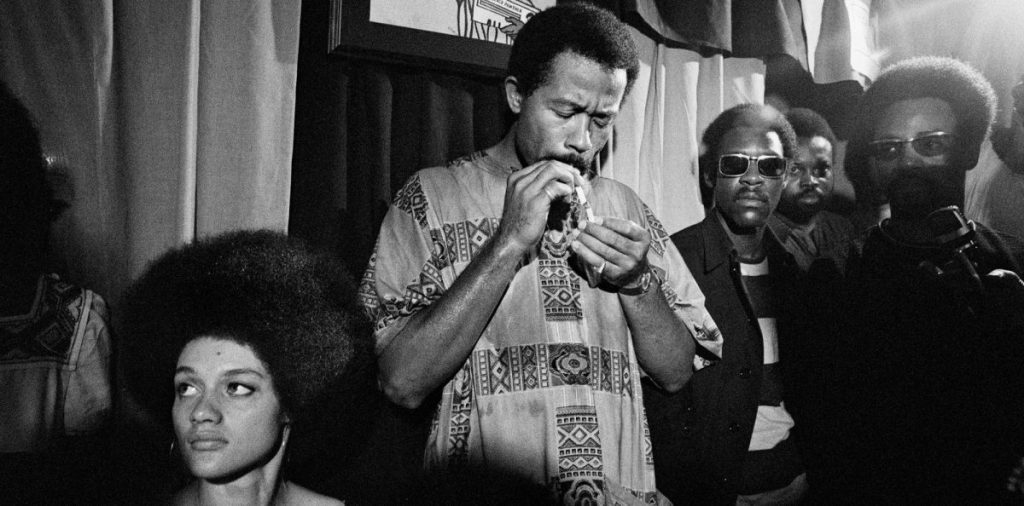

Algiers became the capital of the Third World, and this is what Elaine Mokhtefi, an Algerian American and one of the heroines of Algeria’s liberation revolution, writes in her memoirs published by Verso Books. Elaine visited me by coincidence, on the day my new novel The End of the Third World, was presented in Pittsburgh, I held her hands tight, I loved her at first sight. we spoke at length; history walks on two feet. A woman of steel, and the only living witness to Frantz Fanon’s militant life, as she worked with him hand in hand at the embassy of the Algerian revolution in Ghana, and with many militants. After independence, Elaine Mokhtefi lived in Algiers, where she was able to persuade the Algerian authorities to bring activists from the American Black Panther Party to Algeria, where Algiers became the movement’s global center; in that period, a refuge for many American activists and intellectuals, among whom we mention Eldridge Cleaver, author of the book Soul on Ice, Kathleen Cleaver, Donald Cox, Timothy Leary, one of the pillars of the white counterculture revolution in America. Algeria also received activists from all of Africa and the countries of the South, and supported activists from Portugal, Ireland, Canada, and contributed to bringing down the apartheid regime in South Africa, and trained and funded Nelson Mandela, who states this explicitly in his memoirs. When the West was calling South Africans terrorists, Algeria was granting them passports, as happened with the South African singer Makeba, who sang in Algeria after the fall of apartheid in her country the song “I Am Free in Algeria.” All this and more made the city of Algiers deserve the name Mecca of revolutionaries. Algeria was the original experiment in welcoming activists and free writers, three decades before the start of the ICORN network, and more than four decades before the beginning of City of Asylum Pittsburgh. Everything may have been just a bigger and richer duplicate of ‘Algiers Mecca of Revolutionaries’.

My search for Algeria in Pittsburgh did not end there. When I arrived at this organization, I was the first Algerian writer to reach here, the only Algerian to this day, and I was among few writers whose activism, was largely documented through international and human-rights organizations around the world, including Front Line Defenders, Human Rights Watch, and UN reports. And international recognitions from the German Bundestag, PEN International, and Index on Censorship. All of this drew a great deal of attention to me in America: invitations to several universities and to several events. And given Pittsburgh’s long activist history, workers, steel smelters, and the working classes, and its activist history for women’s rights too, there was something of Algeria’s spirit permeating the smell of the air mixed with iron particles, just like Pittsburgh in Algeria we put fries in our sandwiches, and we think we’re all steelers. All of this contributed to my ability to “surge forward” and express my ideas in this space without fear. And I took advantage of every opportunity to talk about the ills of America’s healthcare system, the homeless, and LGBT rights, thinking that America was the nest of peace I had always awaited. But here, with soft repression that does not speak its name, it was decided to place me on the margins: to stop inviting me, or to besiege me. No invitations again, no attention. And when everyone was talking about their country freely, I would sit with the audience to listen to others, from America, France, and other countries, talking about us, Algeria, Algerians, about our literature, our history and our revolution, about our pains: many mistakes, much indifference to the millions who were exterminated, to the bones of our dead that were used to grind sugar and wheat in France, as Xavier Le Clerc says, and I would content myself with painful applauding.

For just as Albert Camus erased Algerians in his novels, and just as he killed an ‘Arab’, an ‘Algerian, in ‘the stranger’ without naming him, symbolic killing continued to pursue me as an Algerian in America, as if it were a sacred tradition in the West that the Algerian be erased, his character assassinated, and his work attributed to others, because in Algeria their myth of superiority collapses, because in Algeria we write and struggle without asking permission. Here too, to be honest, I have gone through the same mechanisms of oppression, softer but sometimes more painful. I couldn’t find a job: I kept receiving rejections no matter what the job was. And here I am leaving the organization, not knowing what fate awaits me afterward, amid a wave of hatred and absurdity against immigrants, LGBT people, and intellectuals, while I represent all of them. And a lot of ICE this winter. I am cold and afraid.

Algeria said its name again when I heard Trump made fun of our Algerian woman boxer Imane Khelif and call her a man. Elon Musk questioning her womanhood, and the whole west insulting her for winning a battle against an Italian woman, for them she was not a woman because she was too strong, now for them she is not a woman because she is not enough of a beauty. Who would ever imagine an Algerian woman to be a scarecrow in the anti LGBT propaganda in USA? since I arrived here, everything seemed like an illusion.

In Pittsburgh, I have seen Algeria incarnating since I arrived. At Point Park, from above, I saw something resembling Tuareg jewelry (south Algeria), and I heard the voice of ‘my executioner’ in Caliban Bookstore in Oakland, Caliban, who is the son of the Algerian Sycorax from Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest, where the Algerian was presented as a savage person, with no connection to civilization. And I found ‘Alger’ Street named after the Algerian capital, near Carnegie Mellon University, and I ate a couscous nearby, and I met the well-known Algerian writer Amara Lakhous. And all of this ended with a museum like exhibition created by one of the founders of City of Asylum Pittsburgh to celebrate the poems of my colleague, a Sudanese writer residing with us in the program, using Frantz Fanon’s book Dying Colonialism, which talks about the Algerian revolution and Algerian society (original title: The Fifth Year of the Algerian Revolution), and Albert Camus’s book The Plague, which takes place in the city of Oran west of Algeria, where my father and my mother married, and a big a map of Oran on the exhibition’s outer wall.

Algeria followed me here, too. But again, I couldn’t utter its name.

When Algeria started its manifestation in Pittsburgh, I felt Sometimes Happy, sometimes burned out, sometimes sad, and sometimes breathless. My history, my pain, my geography, my ego, my pride, my name, Anouar, often not pronounced correctly in Pittsburgh, all of me was denied. Not because it is my homeland, but because it is the narcissistic wound that exiled me in the first place. Because there, in Algeria, I was told you are not Algerian because you are gay; and here I was told also: you do not deserve to represent Algeria because you’re ‘Algerian’.

Thus, Pittsburgh in its entirety turned into a new Algeria, the same Algiers I left behind, with its beauty and its repression. With its Clementina and ‘iced’ coffee, for I wished Pittsburgh to be a new Algeria, and God granted me my dream; perhaps if I had wished for a billion dollars, I would be fine today, but because I wished for Algiers so strongly, and created it with my own hands, Pittsburgh became a homeland that pats my head and excludes me without realizing, perhaps, or without confessing. Maybe, Pittsburgh did that, just to remind me why I had to leave.

Anouar Rahmani