Salman Rushdie was stabbed. A man stubbed him with all the strength that could be mustered. He was hit, punched, and stabbed repeatedly and with great malice, while I filmed with my phone. I couldn’t believe what was happening; I expected an intellectual and philosophical debate. I was waiting for a discussion about literature, thought, and freedom of expression. I was waiting, in the worst circumstances imaginable, for someone to take the microphone and oppose, rebuke, or even curse Salman Rushdie, not to stab him. All my mental tools were focused on receiving information, not punches. I was very attentive and fully prepared, to the point that I violated the guidelines and moved closer to the stage, away from the other writers, to listen carefully to the meeting so that I wouldn’t miss a word. I was eagerly waiting for Salman Rushdie to appear, and at one moment, the voices began to rise, and the “stabbing” began. The stabbing that has not stopped within me until now.

This happened on August 12, 2022, the same year I came to America. My American experience was still fresh, and my thoughts about this country were still swaddled. My mind had not yet grasped violence in its American form. Like many other immigrants, we initially think we are on a recreational trip and that we have arrived in paradise, before being swept away by the “violencity” of this country (if I may invent this word to avoid saying violence) and finding ourselves facing a new, more complex version of our old sufferings. A different “violencity” from what we were accustomed to in our

home countries, and we lack the experience to deal with it.

If violence were an act, violencity is the method, the process, and the mechanisms in which violence is hosted, tolerated, and structured to prepare someone to be violent. For me, violence isn’t just a surface act; it’s a deep machine. Every violent act is a continuum of a long path of violent acts in the past, present, and future. Violence is connected as a phenomenon in a way that makes the word violence too basic to cover. And what happened to Salman Rushdie can’t be isolated. It’s a product of this machine that has never been discussed as such. And by that I am not taking away individual accountability of any criminal act; however, the criminal is a logical result of violencity that preceded them, preceded religions, ideologies, and ethnicities. Violencity is the reason for violence. It’s also what makes someone able to commit a crime. And it’s necessary to say that, because this paper isn’t Islamophobic and I don’t mean by writing this to use the Salman Rushdie incident to justify hatred toward Muslims and Arabs, what often Western media outlets often do. And my condemning of this crime comes with an awareness that violence is a machine and not an Ethnic or religious Group.

The day before the incident, we went together to Chautauqua, a group of writers from City of Asylum Pittsburgh organization. We were expected to participate in literary activities at this institution alongside the founder of the organization, other invited writers, and, prominently, Salman Rushdie, as well as staff from the City of Asylum organization, including its executive director at that time. We went like scouts, as if we were a herd of writers and intellectuals to this grand event. This was the first time Salman Rushdie personally appeared on stage after years of isolation imposed on him due to the Iranian fatwa that called for his death following the publication of his famous novel “The Satanic Verses.” My back was hurting a lot that morning, yet I couldn’t miss this trip; I wanted with all my heart to meet a great and well-known writer like Mr. Rushdie. I couldn’t move smoothly due to the back pain, yet I forced myself to go; it wasn’t an opportunity that could be replaced, and the organization at that time was very generous in its offerings to writers. They were very kind, and it was somewhat like a group tourist trip to the Maldives. We spent a wonderful night in Chautauqua, a musical, classical night, in one of the most beautiful places in New York State, with many white people, many more than the eye could bear, and a few from “other races,” as Americans would say, in places that were hard to spot. During this journey, I learned many things I did not know about this country; classism became manifest to me in its clearest form at the Chautauqua Institution (not for what it is, but for what it resembles) which is perhaps not an institution in the traditional sense, but a small, isolated, fortified city inhabited “maybe” by the wealthy, and entry was through a “visa”—we stood in line and waited to obtain it. It was a charming place resembling paradise, reminding me of a place I knew well in Algiers called the Pine Club (club des pins), where the wealthy and government officials lived in isolation from the rest of the people, and it had always been tied in my country to stories and mythologies. I am not sure if this place resembles the Pine Club, but I am sure nothing else resembled me in this place. This trip changed many of my thoughts; it made me rebel inside, as if it opened many ideas in my mind that I would not have understood had I not gone to this place. The next morning, I don’t remember the exact time, the »stabbing« of Salman Rushdie occurred, an incident that dismantled me and reassembled me into a self I did not know by then.

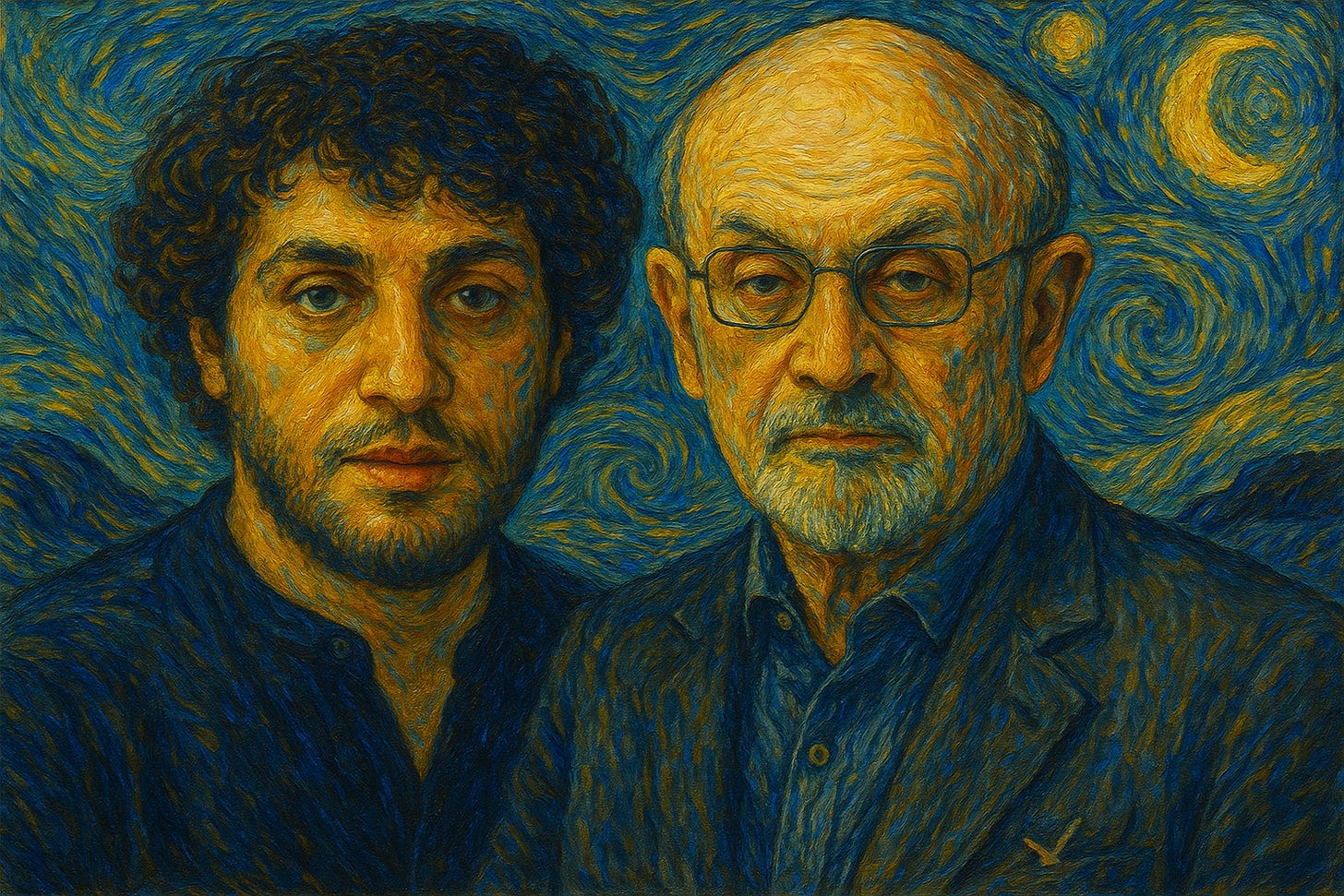

As soon as Salman Rushdie entered the stage with the spiritual father of our City of Asylum organization, Mr. Henry Reese, amid warm applause, and after Salman Rushdie sat in his seat, I looked at my phone to start recording, and as soon as I did that, screams filled the place. I slowly raised my head, and a person was wearing a black shirt, or maybe not, I don’t know, but that’s all I caught sight of, punching Salman Rushdie with force. That’s what I saw, as if my mind could not comprehend that a person was stabbing another person. I saw Salman Rushdie on the ground, and Henry Reese pouncing on the criminal, trying to save his friend. I walked closer to the scene, holding my phone, while screaming: “Oh my God, oh my God…” but not with the intention of filming; what I wanted was to save Henry Reese. Honestly, I was concerned about Salman Rushdie and sympathetic to him, but Henry Reese’s life was paramount, for when I came to America, this man, who is about my father’s age and does not speak much, I felt like he symbolized my father in the new place. (I forgot to hug my father before fleeing Algeria.)

I posted the video I filmed on Facebook and Instagram for my friends, not knowing at the time that I would be the first to convey the news to the media. A few minutes later, I don’t know how it happened, the video I filmed of myself screaming, “Oh my God, oh my God,” as I approached the stage, spread across all news channels around the world. The major platforms and channels rebroadcast the video in America and elsewhere without my permission, and they didn’t even remove my voice, which put me and my family in Algeria at further risk. A Reuters reporter called me for my statements; I told him that Salman Rushdie needed more protection, and that there weren’t enough protection protocols for someone like Salman Rushdie, who had a fatwa issued against him. He conveyed this, but did not report that I asked Americans not to allow racists to exploit this event against the Muslim minority in this country. Because, as a human rights and minority advocate, I understood very well what it meant to belong to a minority in such situations. I felt it was my duty to say this, so I wouldn’t find myself contributing to the harm of another person unknowingly, but my words might have been “unnecessary,” and the journalist did not include them in his article. What mattered at that time was “Salman Rushdie has been stabbed”… stabbed, stabbed, stabbed. That’s all that matters to the Western press: the event, the shock, the news. Neither the philosophy emerging from it nor what comes before or after, and if the Western press graciously unleashed discussions after any event, they are usually long debates where the victim and the perpetrator are treated equally, with the Western ‘person’, of course, taking on the role of the judge in the accountability.

American journalists did not respect my voice, my filming, or any intellectual property I had over the video, nor did they convey my full statement as it was. I felt once again that this West, with all its components, even its journalists, does not see me as an equal human being, but as an event, as something ephemeral, sometimes as a scandal or as news. The victim is nothing but a voice crying out for a back being whipped and cannot be a voice arguing for a thinking mind. This was another shock added to a long list of shocks I have witnessed in the USA. The messages of insults and threats that reached me and my family after the video spread are countless; from the first few minutes until now, they have never stopped, lasting as if they would last forever. People burdened me with the sins of everyone because my voice said, “Oh my God” when Salman Rushdie was stabbed. Because my voice sounded scared and sympathetic to him, and this is unforgivable in the eyes of religious societies. Can someone call upon God to save a blasphemer like Salman Rushdie? More than that, can a blasphemer like me call upon God?

Deep inside me, I knew I was the easiest version of Selman Rushdie for a person to harm, the weakest version of him, institutionally speaking. I do not have the protection tools that Salman Rushdie possesses, nor his celebratory platforms, nor his major publishing houses. If I were to be stabbed in Salman Rushdie’s place, I would not receive the same level of attention, as the classism in the world of intellectuals is brutal, and uglier than the classism of the masses; the latter is based on tradition and succession, while the former is a brutality of the immense size of hierarchies and arguments that the intellectual builds about himself and the world.

I breathed, not to breathe but to avoid thinking more about the reality of what I saw. I took a deep breath, and a voice called me from behind to move away from the stage.

I couldn’t move fast, physically and intellectually. I could not accept the idea, but I absorbed it enough out of necessity, to the point that it became under my skin, like seeds? Emmm, No, but like knives that have not stopped stabbing me since that time.

The stabbing never stopped inside me; I, who was accused of what Salman Rushdie was accused of in my country, saw someone like me resembling me in exile, in some ideas (not all), and opposing religious authority. His story somewhat resembles mine, being stabbed in front of me, deep inside me, specifically in my subconscious; it was Anouar Rahmani who was being stabbed, not Salman Rushdie at all. My mental state shattered; I felt like I was collapsing. The nightmares did not end after that; I could not sleep. There were perhaps hundreds of people in the place, but no one viewed the event from my perspective. I did not see Salman Rushdie being stabbed; I saw a version of myself being stabbed on stage, and when I said, “Oh my God,” my atheistic position that I had always defended dissipated, and I found myself in a philosophical and ethical situation greater than merely witnessing another writer being stabbed. I saw many of my certainties, my dogmas, and my thoughts collapsing. As my fellow citizen, the Algerian Jewish philosopher Jacques Derrida might say if he were in my shoes, “I deconstructed and reread myself.” Even my most rigid positions may have shattered from me, and I became a more fluid being than ever. The West then allowed me to be a witness, but can I, as an intellectual exiled from the Global South, be more than that? Does this West, with all its racist arrogance, allow me to be a thinker, a theorist, an analyst? Does it allow me to be more than just a piece of news? Does the exiled have the right to be a voice, not just a crying face, one that thanks and remains silent? Or does exile have its framed voice that we must not deviate from, that voice, light, heavy, and filled with expressions of gratitude and sacrifices…

Some journalists tried to contact me after my first statement, as I was the first to convey the news to the world through the video, but City of Asylum asked me to remain silent and not give any further statements to protect me from any legal issues or even local threats. They were right; an American journalist, for example, tried to bait me with her question to build a report that might accuse me, maybe, or city of asylum of any charges that would burden me/us with more legal problems that I was better off without. When I did not give her the answer she was looking for, she hung up on me rudely and angrily, as if it were my duty to be foolish as a migrant from the South. Another journalist, whom I considered a friend in France, recorded me while I was talking to him without informing me. I told him I did not want to publish the interview because I was talking to him as a friend, not as a journalist, and that the organization had asked us to remain silent. However, he refused that and published the article against my will, telling me that French press law protects him. I found myself caught in a whirlwind of violence that did not seem to ever end. The world was very harsh around me; I did not understand whether I was in reality or in a nightmare. Many sacred things in my mind were shattered at that time. The press itself, which I had always been a child of and defended, once again became an instrument of oppression. The Jewish Family Services Center in Pittsburgh offered to follow up with me psychologically after this trauma, and since then, I have been trying with the help of this center to gather myself again and push myself to write, after the incident with Salman Rushdie deprived me of sleep, writing, and my dignity.

How did I come to America?

On January 4, 2022, I left Algeria reluctantly for America, the country of exile that I did not choose, but rather it chose me. After years of persecution in Algeria due to my ideas, my political articles, especially the satirical ones, and my banned novels that led me to interrogation and judicial offices, as well as my defense of human rights, freedom of expression, LGBTQ rights, same-sex marriage, women’s rights, and minority rights. I had no choice but to “escape” as I was not as brave as I thought I was, especially when I saw a young Algerian named Djamal Ben Smail being stabbed and burned alive by a mob a few months before I boarded the plane. I found thousands of Algerians being dragged to courts because of their opinions about the new president, Tebboune. I was afraid; I was a coward. I packed my bags and fled, with the help of Artist Protect Fund, an organization based in New York, and I was very selfish for doing this, something that exiled writers do not often admit, but I will say it despite myself. I chose exile for myself, not for the homeland or the people. I left because I wanted to survive; I left because I was, frankly, “a coward.” It’s okay; sometimes one must be a coward to continue living.

I did not choose exile as an act of heroism as many writers want to convince me; fear made me flee—fear of imprisonment, of murder, of death, of torture, of betrayal, of the possibility of being used as a pawn against the Algerian people, especially because of my leftist ideas supporting LGBTQ rights, women’s rights, and religious and intellectual freedoms. I feared that Tebboune would crucify me on the stakes of the Algerian moral court to gain some popularity. I knew in my heart that he could do this; he had previously tried me in a year-long trial because of a satirical video, then interrogated me about an old article I wrote titled “God is Free,” where the police officer at that time told me that God is not free and that this was blasphemy. I laughed and said, “So God is no longer free?” He replied, “God is not free because freedom is not one of God’s names, which number ninety-nine.” At that moment, I understood that prison was no longer just a building but an abstract idea in which God Himself could be imprisoned, so what about humans? The new mythology that the ruling authority sought to create around the new president was completely different from the previous president, Bouteflika, the president of reconciliation and forgiveness. Tebboune, the new president, was meant to be the president of punishment and fear, not the president of peace. When I understood this and realized that God was also no longer free, as the officer told me, I was certain that I was in a dangerous situation that I could not ignore, and that the era of Tebboune was completely different from the era of Bouteflika. Tebboune did not want to be a president for the people but rather a president over them, a president despite them, or at least that was what I thought at that time.

I was a coward to the extent that I hid my decision to flee from my family until the last week. I was afraid that my secret would be revealed, and I would be prevented from traveling, as happened in 2017 when I was banned from traveling to Lebanon and was placed in airport detention, then taken from one place to another throughout the entire day. I was scared, and I also knew that hiding this matter from my father, mother, and siblings was a psychological crime against them, for in Algeria, family is everything. Family ties do not weaken over time; rather, they strengthen, and we do not leave the family nest quickly. The Algerian family is a nurturing family; it’s a forever nest. I found myself in a moral dilemma somewhat similar to the dilemma where you are asked to choose while driving a truck without brakes: to crash into five people on the right side or one person on the left side. I did not have time to think; I chose to ignore both options and jumped from the truck to save my life.

When I told them, their shock was profound, but they did not stand against me; instead, they encouraged me. Something inside me that pushed me to emigrate was also due to their sad faces. Every time the police knocked on our door looking for me, or every time they read those articles that distorted my reputation in the most widely read national newspapers in Algeria, which harmed me greatly. I knew in my heart that distancing myself from my family would spare them the burden of fear that I caused them because of my “intellectual selfishness.” Seeing them sad was easier for me than seeing them scared, as sadness, believe me, is much better than fear.

In the last week, my mother cooked everything I loved to eat, and my father gave me a hundred dollars, which was all he had. On the last day, I ate my favorite dish, lentil soup with semolina balls cooked with herbs from the forest. This traditional dish from my region has always been my favorite since childhood. My mother prepared it and sat in front of me, watching me eat, while all my siblings and their children looked at me, just as I used to do when I was a child, when I fed my rabbit, watching it chew. They were watching me chew the food; in reality, I was pretending to chew and eat so that my mother’s effort would not go to waste. And to avoid looking sad, in such farewell situations, one must appear happy even if they are not, so as not to make them more sorrowful than they seem. My smile floating on my face was like the image of the moon floating on the sea’s surface in our city’s harbor at night, which I for long enjoyed. Smiling was the only evidence that I was doing what I chose, not what I was compelled to do. My mother had to see me happy so that sadness would not dwell in her heart while I looked sad in front of her.

My father was waiting for me then, with my brother in the car outside, to take me to the airport. I stood and hugged everyone. Everyone was crying as if I were seeing my own funeral while I was alive. One after another, everyone hugged me while crying. My sisters, their children, my mother, my brothers’ wives, everyone was crying. My sister, Nassibba, hugged me, her body trembling; I could never forget her crying. My sister Leila, whom I left heartbroken after her divorce, and my sister Wassila, who had just lost her hearing but had not forgotten how to listen to me as I bid her farewell while she cried. My sister, Djamila, and her children, my brothers’ wives Karima and Maryam, everyone. It was an indescribable feeling. In Algeria, it often happens that people are exiled because of their ideas, and they usually do not return. We have become accustomed to this in Algeria. For example, Ait Ahmed, the founder of the Algerian revolution against French occupation and the founder of the first opposition party in Algeria after independence, lived in exile in Switzerland until he died, having liberated a country he could not live in. And just recently, as I write this article, the representative of the mothers of the Disappeared, who were kidnapped during the civil war in the 1990s in Algeria, was informed at the airport while returning to Algeria that she could not return. Why? Because, as a mother of a missing person, she innocently asked them, “Where is my son?”.

I rode with my brother, my father, and my nephew, Ihab, in the car, heading to Houari Boumediene International Airport. My father was tense, his face red, suppressing his tears. I also held back my tears; I was playing the role of the happy one. Deep down, I knew I had truly hurt them, due to my recklessness at times, and because of my writings that had entangled me more than once and dragged them along with me. I was an insane, selfish, wanting-all writer; I wanted to be a writer despite everyone. I imposed myself and my name in the world of literature and thought in Algeria, in a country where it is difficult to gain recognition as a “writer” or philosopher, in a land that has given: Saint Augustine, Lucius Apuleius, Ibn Khaldun, Kateb Yacine, Mouloud Ferraoun, Albert Camus, Assia Djebar, Frantz Fanon, Mohammed Dib, Mammeri, Jean Senac, and others who do not easily grant titles to their elites, not to mention the thousands of obstacles created by the political authority in Algeria against intellectuals. But I did it; I imposed myself by force, with courageous words, and a lot of stubbornness. But after what? After my life was lost, no job, no life, fear always consuming me from within, no friends, no loved ones, and my family had become unbearably miserable. I felt regret; I do not hide this: “If time could go back, I would have settled for eating, drinking, and sleeping. As for ideas, like any smart person in Algeria, I would have whispered them to my pillow before sleep instead of telling them to the world, and nights would always end with a new morning.”. I was stupid, as I said nothing to my pillow; the morning never came. This is precisely what I was thinking at that moment as I contemplated my father’s sad face in the car’s front mirror while sitting in the back seat.

My brother took a wrong turn, and I was late for my flight. I was neither sad about this nor happy. My feelings were neutral, as if I were not myself, as if I were a character from my “trivial” novels. I arrived at the airport late, in the final minutes before the plane took off, which facilitated my escape. When I reached the airport, the place was empty. I approached the customs officer to board the plane, who was near its door. My father was watching me from a distance, sad. I handed my passport to the customs officer. He searched for my name and information on his computer and found that I was banned from traveling (political ban). He did not understand what was written, as it is usually presented in the form of symbols. He looked young, perhaps new to the job. I thought of deceiving him; I tried to converse with him and convince him to let me go, and the plane was about to take off. I was on edge, but I didn’t want to beg him because if I did, he would surely know that I was hiding something. I had lost hope. At that moment, another customs officer came, as if the heavens had sent him to save me. I saw him approaching; he was also young, perhaps in his early twenties, handsome, elegant, tall. I would have fallen in love with him if I weren’t going to America. He went directly to the customs officer holding my passport, said to him, “What’s wrong?” The other replied, “I don’t understand what this symbol means, maybe national service…” He took the passport from his friend’s hand, stamped it for me, and said, “Go to America and live your life.” From a distance, I signaled to my father that I was leaving, and my friend Hamoud was with him, crying. I saw my father rubbing his eyes; I wasn’t sure if he was crying or just rubbing them, but I felt he was crying. My father does not like to appear broken; in Algeria, men do not cry. I did not cry; sadness nested within me, but on the surface, I felt somewhat happy as I boarded the plane. It was just a few moments of happiness before entering the plane. A man passed in front of me and perhaps said, “Don’t you dare come back…” or “Don’t do it again.” He continued walking; I observed him without paying attention, boarded the plane, and the door closed behind me as I was the last to board. At that moment, Abdullah Tamam called me, a man in his sixties who had lost his legs in a train accident in Germany while studying there when he was 20 years old. He was sent back to Algeria, and when he demanded his rights, they imprisoned him for ten years despite being legless. From 2013 until my last day in Algeria, he was my best friend, he and an artist named Hatem Hemis, and an activist named Kiti Hammoud. I hung up the phone when the plane began to take off. At that moment, I remembered that I had not hugged my father, and I burst into tears. I saw the plane leaving Algeria, and I couldn’t stop crying. My father’s embrace became my psychological knot since leaving Algeria; I fear I may never hug him again. Since arriving at the organization, every time I see Mr. Henry Reese walking, I remember my father.

If my brother hadn’t delayed in the car, if I hadn’t been the last to board the plane, if that young man hadn’t come to save me at the last moment, I might have remained trapped in my suffering in Algeria. Sometimes, coincidences are stronger than miracles. And small things done by a person can change the course of many people’s lives. Change, as I always argued, is abstract, there for it doesn’t have to be big as an amount, it’s there, like a butterfly theory, small changes in the air can change the whole world.

Months after arriving in America, I was tried in absentia in Algeria and sentenced to a year in prison. Why? So that I could never return to Algeria. As for America, the world was different, wonderful people around me, helping me, staying up to reassure me, and at Carnegie Mellon University, which was my little paradise, I met a new academic family and studied again, not to learn, but to forget…

A few months after I arrived in America, my nephew, Ihab, was stabbed in the neck in Algeria by someone riding a motorcycle, perhaps because of me; perhaps I’m not sure, but this “perhaps” is more painful than anything else. My nephew remained in the hospital and was near death, but he survived, and I was unaware of that. Nobody told me. Until I learned, from my niece, just right after Salman Rushdie was stabbed, and my nephew was finally alive and doing fine.

The violence never stopped; my sister also faced violence from her husband, perhaps because of me as well. Two of my friends in Algeria contracted HIV. In Pittsburgh, there were shooting incidents, then the Salman Rushdie incident, and then two years after that, my Sudanese-American friend named Shiber was found dead in the river, and despite his death, he was not spared from racist comments on social media accounts.

Another violence that I noticed in this country is the violence of denial. In America, I saw a repressed people, also without social rights. The richest country in the world and the one with the highest number of homeless individuals. Good hospitals with a class-based health system. A rich and corrupt state at the same time. It took me thousands of kilometers to dispel another myth from my mind; the West was not the promised paradise. The West is corrupt and wealthy, racist and consumerist. The Western man is a sick man, just like our Algerian man. The type of illness differs, but both are sick. However, the most heinous form of violence is the institutional denial, an organized denial with mechanisms that can only be described as “hypocritical,” often using our voices, we, the exiled from other countries, to justify the catastrophic and unjust situation that Americans living in.

Violence, so much violence, since I arrived in America, poor treatment from some restaurants, color sensitivities, and when the war started in Gaza, no Arab or Jew in this country was spared from linguistic and physical manifestations of violence. Renewed forms of violence appear and disappear on reels, on TikTok, Instagram, and everywhere. With all this violence, the knife that stabbed Salman Rushdie began to dissolve little by little inside me, opening the space for me to think about the “violencity” behind it.

Is it violent to be an exile?

When we flee, we violate the law, the social pact, the national herd. We decide, until we don’t, to be traitors of the national pride. It is violent to be an exile. And this violence/violencity is not merely metaphorical. Violence is what made us exiled in the first place.

In this article, I do not wish to be ungrateful; rather, I want to add a new meaning to exile as a mechanism, a violencity and an apparatus, which, once Michele Foucault called “dispositif” and not merely a state, a metaphor or a humanitarian case. I want to truly take it out of its literary and magical guise into a real and mechanical-like world that functions through mechanisms and dynamics. Exile as a mechanism does not necessarily mean a bad mechanism; rather, it can be a mechanism of power. Perhaps it is not always a mechanism of oppression, but sometimes it is also a mechanism that pushes the exile into ingratiation, flattery, and wooing, inside a hypocritical, weaponized system.

In this country, I went to more than one university, more than one school, more than one organization, and over time, I understood that there are mechanisms governing the world of exile. A psychological machine, sometimes repressive even in the most radiant images of mercy. The white man in America chooses who should speak and who should remain silent among the exiles. Soft tools of repression that do not seem like repression at first, because it is not the type of repression we are accustomed to; it is a much smarter form of repression. And to avoid paranoia, let me acknowledge before I continue this article that most of the people I met in America, especially in City of Asylum, Carnegie Mellon University, APF, icorn, and others, were sincere in their feelings and their desire to help, and therefore, I have to admit that this article isn’t about them. The machine is not the individual. Some traditions are followed even in the most progressive institutions, and they can never be bypassed. The kindness of individuals sometimes cannot overcome a machine that has settled in the consciousness of the West for centuries, along with a set of racist and homophobic, transphobic and anti-Semitic traditions, anti-Arab and anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, and anti-women sentiments. Ideas that are clearly found in the works of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Darwin, and other founding fathers of modern Western mentality. I wanted to write this article not to say everything but to hint, because after all these years, I am still afraid.

This is what I learned from my experience in exile and the incident with Salman Rushdie (self-criticism):

It seems like a survival at first, but it quickly turns into a project, and with it, the call for help transforms into a suffocating voice. The loudspeakers that the exile longs for become instruments of interrogation, the outstretched hand turns into a silencing palm, and exile is framed in colonial and orientalist molds with anticipatory tools that are no less authoritative than those that originally drove the intellectual into exile. Amidst this turmoil, the obeying intellectual emerges, approaching colonial perceptions and reproducing them within the victim narrative—the eternal victim who has escaped from the world of savages, the world of barbarians, the wise survivor from a realm of less human beings, from the degraded human world, the less civilized, the less refined, the morally disturbed, and the incapable of thought. And when the picture becomes clear, the exile then faces two choices: either survival as a natural act or survival from survival as a political stance that may threaten his existence, threaten his selfish image of himself as an intellectual, and make his survival merely a symbolic metaphor, suffocating within the Western institutions eager for the voice of the drowning, the dying voice, and the self-reproaching conscience—the voice of nails scratching the ship of salvation, the ship of the West, the voice of nails clinging to the boats and cries for help. For the greatest Western pleasure is the pleasure of hearing the voice of distress emanating from the East or the South, the voice of the lower victim, the degraded victim seeking salvation, salvation from the world of savage victims, the world of the South, the South that lies beneath the earth, the subordinate South or the magical East. The call for help that makes the Westerner don the role of the savior, the superior role, the rational role that he desires, which entices him, justifying his condescending argument first to himself and then to the victim. For one who extends a hand to save from the top of the ship is not like one who is beneath it as a victim, submerged in the idea of sacrifice.

Exile, even if voluntary, is a political experience, even in its simplest forms, an experience that can be described as a form of opposition, the most radical one, and it is also the most selfish. When the helpless intellectual is forced to flee, he thereby acknowledges that he will not sacrifice himself for his community and people. In this case, exile is not just travel or crossing; it cannot be simplified to the name of immigration, for the immigrant does not seek recognition but stability. The exiled intellectual, however, is in constant need of recognition, as if the whole world owes him and his great sacrifice of fleeing his homeland, convincing himself first and then others that escaping is heroism, a brave intellectual achievement, forgetting that the back does not possess the faculty of expression, and when we turn forward to go our own way, it is because there is nothing left to say. But the intellectual is a creature of excuses, always searching for justification, with an answer for every question. And since exile is a political step, it must have justifications, arguments and an intellectual solid, as if all the excuses in the world meant to justify his decision to flee, as if fleeing, that shameful act in the lexicons of struggle, were merely a form of sacrifice or self-repression, as if it were an act of mysticism, a spiritual act that only prophets can achieve. An act that most people are incapable of, not because of the queues for visas at Western embassies but because of the ability to jump and survive as an act of an intellectual, an act that is not a matter of improvisation or the nature of the situation but a bold step taken by the intellectual to turn his back on those he once sang about culturally and defended. But fleeing is merely a response to the call of nature, the call of the survival instinct, and there is no heroism in the song of people sung by heroes while they are still alive.

The exile that seems like resistance at first will, over time, seem like escape, then turn into a fall. And when the exiled intellectual begins to fall, he will not initially know whether he is falling upward or downward, whether he is falling or flying. For when the depth of the pit is very deep, surrounded by darkness, the fall will not be seen, no matter how frightening, except as a process of relaxation in the air. And thus, with the fall, the image of the intellectual about himself inflates, the submerged intellectual, seeking once again for recognition, that of the “white intellectual master.”

The Narcissistic Wound of the Intellectual:

The Italian philosopher Gramsci theorizes from his prison cell that all humans are intellectuals, then he corrects himself and says that they are intellectuals insofar as they can think, but only some of them activate this characteristic (by my own words). I see that he thus makes intellectualism an inherent act that only surfaces through the force of will. This is indeed what the intellectual hates to hear: to be similar to others, to be the version that has chosen, of its own free will, its critical role, its cultural role, its sometimes-visionary role, and not that cognitive uniqueness that makes it distinct from others. Distinction and recognition of this distinction, of the uniqueness of its voice, of its genius, intelligence, and the validity of its perceptions and ideas. This quest for recognition may entangle the exiled intellectual and may reduce him to a limited set of ideas, transforming him from a thinker into a tool of political propaganda, sometimes a tool for colonial, racist, and abhorrent orientalist ideas, perhaps not of his own free will but by what nature dictates to him. The exiled intellectual is a broken person, usually lacking the same rights as the masses; in the new land to which he has been exiled, he possesses only some civil rights, and he must strive for years of exile to find what makes him equal to others. A narcissistic wound that cannot be easily overcome. The exiled intellectual usually views himself with pride, as he who left his homeland in search of life as a migrant, and in search of recognition as an intellectual, finds himself in a lower position than any citizen in the new land. He finds himself like a reed blown by the winds, swayed by the political developments in so-called ‘Western democracies’. This changing structure of social and political status and the fluctuations that occur make him constantly seek what compensates for his inferiority complex in the new environment by searching for what makes him not only equal to others but better than them through rhetorical tools, sometimes justly and ethically, and at other times through sycophancy to institutions and figures that find in the exiled intellectual what they seek as proof of the validity of their ideas.

Thus the Exile is politicized and thus becomes a trade in the market of discourses, as the exiled intellectual sells statements without a clear contract for buying and selling, but through understanding the game and engaging in it; he is the one who understood from his first experience in his original homeland that opposing the powerful, the dominant, the ruling authority, and society makes him an easy prey for the forces of police, intelligence, religious men, and community members. He realizes, after understanding the political discourses in his new homeland, the land of exile, that the West is not a place devoid of power, whether social, political, or religious, as he had expected, but that the new power governing the discourses of the new land possesses

more intelligent and less direct techniques of repression. As Michel Foucault thinks, wherever there is a rhetoric, there is an authority, and I would add that where there is discourse, there is an intellectual, and if there is no intellectual to fill the power ‘reservoirs’ in the new land with discourses, then one must be created, either by nurturing the local organic intellectual or by importing intellectuals who serve agendas that the local intellectual is ashamed to adopt. The new authoritative discourse in the world of exile tempts the exiled intellectual and makes him adopt the most extreme discourses, perhaps not necessarily out of belief in them, but to showcase his competence in mastering the role he has understood after a long psychological struggle with the mechanisms of exile within Western institutions.

The Centrality’s illusion of the Exiled Intellectual and the recognition as a trap.

The intellectual travels to exile carrying with him a set of ideas about himself and the world; he carries his history, culture, and thoughts and journeys with them to a new land in search of safety, freedom of expression, and recognition. Above all, he carries with him his “centrality,” fundamentally and without any room for revision or criticism, his centrality in the story, not just in his story, but in the story of the world, heroism, and the idea of the victorious victim. His eternal centrality later will make him an organic intellectual in the new world; that trait he has always rejected in his homeland, he will wear in the land of exile, perhaps reluctantly and dreamily like a necktie, for the sake of recognition, publication, and awards. Through the previous experiences of exiles, he understands in their sequence that the only way to gain recognition will be to align with the discourse of institutions and transform into an intellectual pawn. That pawn, harnessed to the silly theories that quench the Western being’s thirst for recognition, is met with the recognition of the superiority of this being, which corresponds to the recognition of the exiled intellectual, recognition for recognition within a closed, complicated game wrapped in many aesthetic and linguistic metaphors that are beyond reproach, which themselves operate as a cover over a well-oiled mechanism for exploiting the victim and rotating him in the political discourse in the West.

Often, the exiled intellectual finds himself between a rock and a hard place, between the hammer of a denying authority in the homeland and the anvil of an authority that reproduces the authoritative discourse, but with soft colonial mechanisms. Escaping from an oppressor dressed in the garb of oppression to another oppressor dressed as a savior, places the exiled intellectual in an unenviable situation, either to resist again and return to a homeland that has prepared for him in advance the garment of betrayal to wear while his hands are bound, or to succumb to the new dialectic and become a soulless tool, conforming to the Western narrative without critique, to protect himself from the exile of returning home and from the exile of exile per-se.

The exiled intellectual approaches all this with the idea that he is the center of the universe, an idea he knows deep down is not entirely true, but the enormity of the situation, the fear of what is to come, and instinct make this idea grow rapidly within him until he loses any ability to relate to the external world; the other is nothing but a testing ground, a subject of study, and an additional character in a world where the intellectual is the center. In this way, perhaps consciously or unconsciously, the exiled intellectual enters a phase of self-worship, self-cult.

Self-Flagellation:

My fellow citizen, Frantz Fanon, speaks in his famous book “The Wretched of the Earth,” recounting his reflections from the heart of the Algerian revolution, that the intellectual from the colonized countries often sees the colonial elites as role models and will try to compensate for them. As an Algerian, I assure you that Frantz Fanon’s theory is correct; after we expelled the colonizer, our elites invaded us with the same methods. It is an inferiority complex, the complex of the foreigner, a complex that Edward Said also discussed from another perspective, but it is the same complex. In the context of exile, what is colonized is not the land but the idea.

When an exiled intellectual arrives in the West, he quickly understands that the only way to succeed is to sell his voice to the machine, to the dispositif, in exchange for publication, media publicity, and what we previously called “recognition.” However, there is another complex that afflicts the intellectual, greater than just an inferiority complex. It is what I call the complex of ‘the fracture’. The intellectual always tries to prove to the people he left behind that he was a great loss to the homeland, which is a legitimate ambition, but what sometimes corrupts him is arrogance and the anxiety of striving for status. The attempt to prove his worth is not by creating genuine intellectual value, but through media appearances, awards, and tools of recognition, while completely detaching himself from what connects him to his previous community.

I have met many of these individuals to the point that I almost became like them. I saw them flogging themselves and their people, writers from oppressed countries, the global south, the east, and others, exploiting their platforms to trample on their peoples. I saw Algerian writers lash out at their people multiple times on French television, our historical colonizers. The most horrific descriptions, the most atrocious words, self-flagellation of the Arab self, the Amazigh self, the Muslim self, the African self, and I saw journalists laughing in front of them, enjoying and relishing the sight of an Algerian flogging himself. Over time, flogging was no longer enough, so they continued to lash out at themselves more, for the white man is like fire; the more we feed it, the more it asks for more.

Today, my fear is falling into that same humiliation and degradation. I admit I have lowered myself, at times, in search of a way out. But I have learned that nothing satisfies this mythical Western being except erasing yourself entirely—your history and ideas—until you kneel before him and accept a subordinate place.

There is a veiled Orientalism even in the best Western institutions. There are superficial approaches in some cultural circles and a horrific exploitation of the exiled intellectual. There is ideological pain, intellectual pain, and more than that, an intellectual suffocation that the exile receives when he understands these mechanisms. The exiled intellectual then understands that the ‘self-flagellating-self’ is better than the “slaughtered” self, as the exiled intellectual travels carrying with him one fear: the fear of the past, but in the West, this single fear turns into two fears, a fear of the past and another of the future, a fear of a harsh authority manifested in his homeland, and another authority that can never be resisted, which he finds in the West; it is the authority of the savior, the authority of moral superiority, the authority of the soft hand, the authority of imposed betrayal, and the betrayal itself as a tool of survival, a betrayal adorned with many praises. And thus, I do not absolve myself, nor do I accuse everyone.

What happened to Salman Rushdie was not just a stabbing, but it was also a decisive moment in my intellectual journey. I understood that I want to be a writer, but not at the expense of others; I want to empathize with Salman Rushdie without adopting all his ideas. I want to critique my society without flogging it, and I want to thank those who “saved me” without worshipping them. I do not want in any way to exploit my story to cover my voice over the pain of other victims, nor do I want to be part of a repressive machine, either in Algeria or in the West. I don’t want to be the servant of the colonizers.

“Exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience.” With this phrase, Edward Said expands the concept of exile to transcend being a mere abstract intellectual classification, becoming an embodied experience of human suffering. To understand exile, one must humanize the exile. For Said, exile is not just a metaphor; it is a fractured reality that requires a dual reading: emotional and critical.

This approach has formed a significant part of the contemporary discourse on exile: experience precedes theory, and the exiled comes before exile. But what if exile is not just a personal shock or an existential rupture? What if it is also a productive device of power, or a Dispositif, that organizes the exiled’s vision, movement, discourse, and institutional recognition, especially in contemporary Western contexts?

Through this article, I rethink exile, not as a tragic emergency incident but as a structuring mechanism of power. From my experience and through a Foucauldian lens that I have not articulated, and by re-reading Said’s theory on Orientalism and exile within this framework, I claim that contemporary cultural and literary institutions do not merely welcome exiles; they actively participate in the construction of the “exile self,” and ‘sometimes’ transform it into a tool for reproducing oppression, with a precise methodology, within a political apparatus of domination and this is no less violent than the incident of the stabbing of the exiled writer ‘Salman Rushdie.’

How many exiled writers have been stabbed without a knife?

Anouar Rahmani: (with much thanks to City of Asylum Pittsburgh, my safe haven in the United States)